Diversity in Organizations (D9)

The aim of this note is to “prove” that diversity and inclusiveness are essential if organisations are to thrive.

Summary: gender-diverse interactions—such as those between males and females—enhance both formal and informal value exchanges within organizations. These interactions introduce varied thinking styles, improve informal collaboration (like spontaneous knowledge sharing), and influence intangible deliverables like innovation and trust. The post highlights that differences in how male and female brains work can catalyze self-organization, creativity, and collaboration, ultimately boosting organizational performance— especially when such diversity is actively encouraged.

The challenge

An issue of concern today is diversity in organizations and inclusiveness so the links to these two words are provided for clarity.

For simplicity we can assume that diversity creates the potential for different opinions and ideas to be expressed, and it is inclusion that allows that potential to be realised. The achievement of this combination could well lead to a transformation in the way in which an enterprise’s organisation and its associated value network and business ecosystem behaves and performs and achieve outstanding success.

Hence, to achieve such a transformation, it is consequently necessary to recognise and encourage the value of diversity and inclusion when people do come together in order to identify and formulate future action. The aim of this note, therefore, is to “prove” that diversity and inclusiveness are essential if organisations are to thrive.

However, what seems to be missing is a way to incorporate the above into a simple framework that describes how organisations really do operate.. In particular, how value is created amongst the participating parties and how behaviour can affect the outcome.

Preparing the way.

Imagine that you are in a work situation by which I mean that you are liaising with others to achieve a particular outcome. You are in a department or a particular discipline within a project or ongoing operation working on a task with colleagues. You may have a job title with roles and responsibilities defined requiring the completion of many activities performed in sequence or randomly. The sequence may be repeated in which case a formal process may have been developed and stipulated which has to be followed and monitored accordingly.

But, as we know, most processes are behind the curve of what really needs to happen and are deficient in one way or another such that assistance from colleagues in the department, team or elsewhere may need to be sought. A manifestation of this behaviour is of course conversations held at the coffee machine or water cooler, even Zoom!

For simplicity, let us envisage that we are in a bubble or nodule with a given or assumed role.

Further assume that all you need is also included. In particular, all the activities you perform and all the assets required to undertake them.

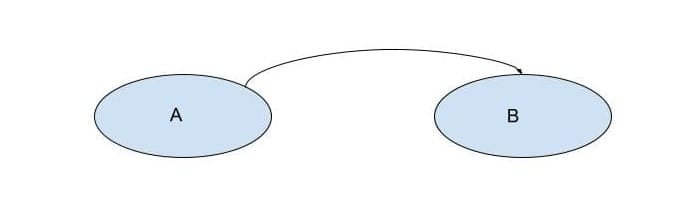

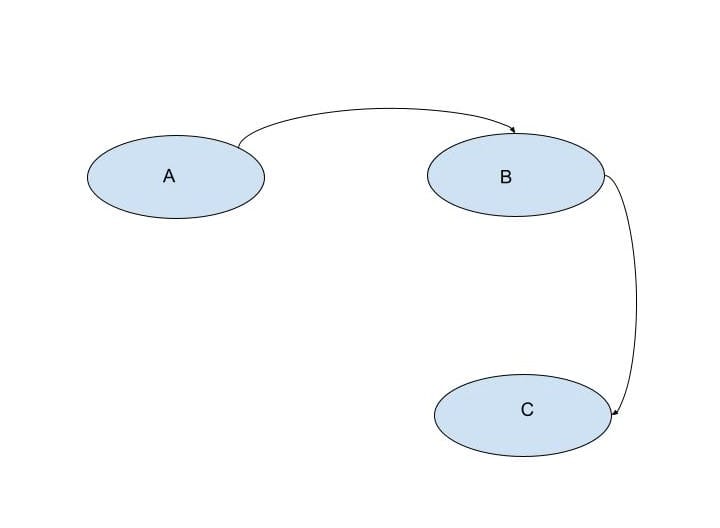

Next, assume you interact with others who fulfil a different role and their focus on what is conveyed between you. A is conveying to B via some mechanism (speech, text, van, ship etc) something of value. (B may not perceive it has value, but we’ll cover that later.)

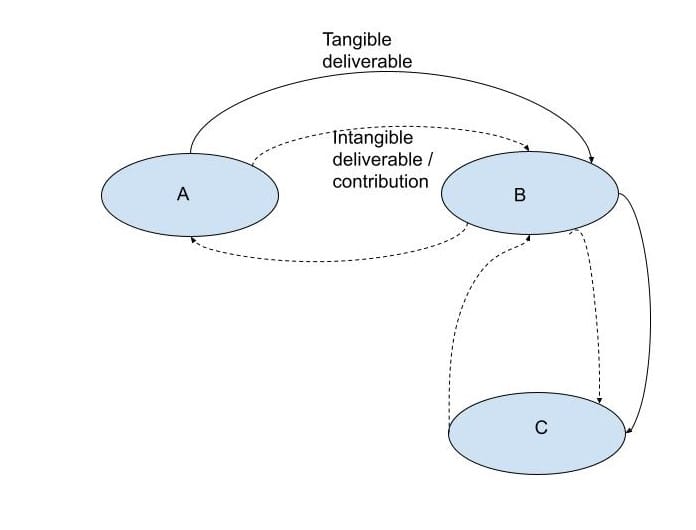

In turn, assume that B conveys to C something else of value. If C is expecting this, let us call it a deliverable transacted formally which is most likely to be something tangible, such as money, services, goods or even facilities.

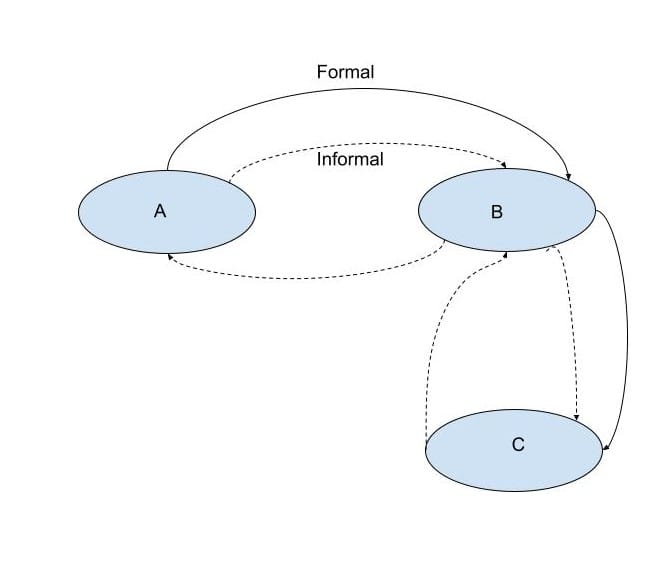

In doing this A and B, via their activities, can either add value to the deliverable or simply transfer it unchanged to others. But as it is a formal process, they have authority via their responsibilities to undertake it - having been granted “de jure” authority.

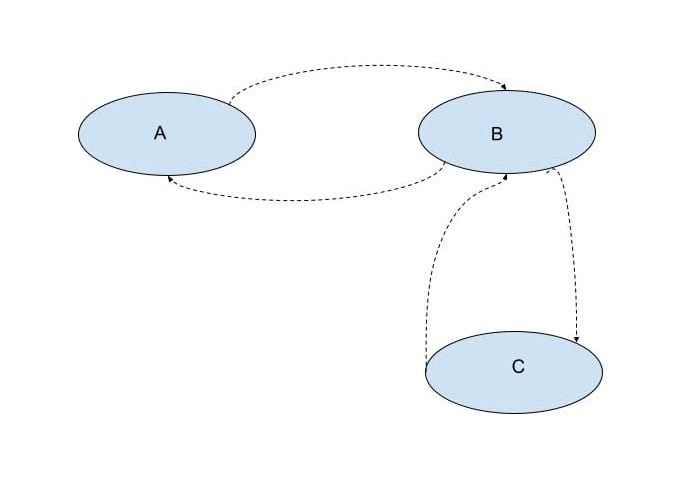

However, not all deliverables are tangible. All organizations, particularly in start-ups, are laced with deliverables transacted informally (think coffee machine or water cooler conversations, or participation in communities of practice or interest groups) that weave between those transacted formally. These deliverables are predominantly unexpected and non-contractual such as favours, unsolicited customer feedback, tacit knowledge and know-how etc and are designated intangible.. Since it is not mandated that A or B contribute in this way, there is no “de jure” responsibility or authority. Instead they are more spontaneous and any authority manifesting is considered “de facto.”

These intangibles are directly associated with informal networks (and somewhat confusingly with “social” networks, as they are not necessarily social, but business oriented.)

Hence, organizations can be represented as a mix of formal and informal value transacting linking Participants’ People and Roles.

A key point is that the resulting deliverables will have an impact on the activities of the recipient, and hence, the deliverables that they, in turn, pass on. Equally critical to overall performance can be the behaviour that People exhibit. This is especially so when intangible deliverables are conveyed.

The “proof.”

We can now link together Participants with responsibilities (associated with de jure formal value transactions), and deliverables (which can be either de jure - manifested tangible, or de facto - manifested intangible.)

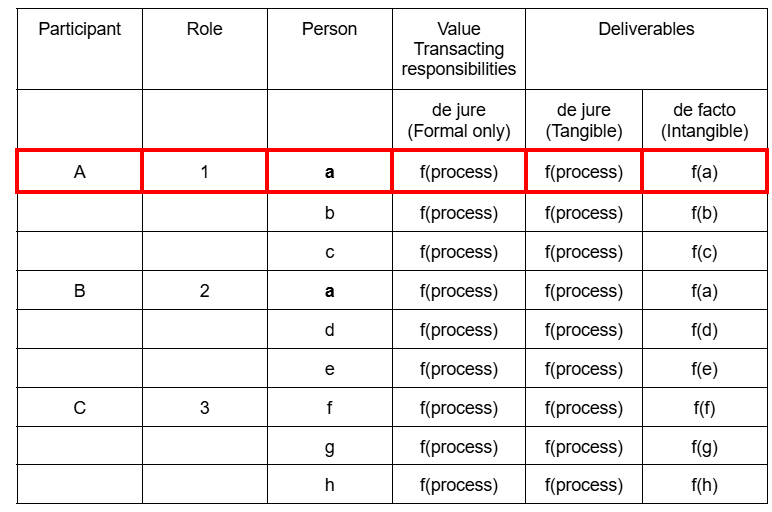

The above table shows the composition of Participants A to C as a mix of Roles 1 to 3 and People a to h. In this example, “a” has two Roles, 1 and 2.

The entry f(process) simply means that the responsibilities are a function of the process containing the value transacting activity.

In the Deliverables columns f(process) means that the Tangible deliverable is largely a function of the process and less dependent on the behaviour / interests etc. of the Person. Critically, though, f(a) etc means that the Intangible deliverable IS MAINLY dependent on the behaviour etc of the Person.

Hence, for the highlighted Participant A, the designated Role is 1, and the people fulfilling it are “a” with “b” and “c.” They are all following a formal process with defined or understood responsibilities and the scope for deviating from them is low. In a fully automated process, there would be no deviation when it is working, and in “lean” operations a key aim is to drive out deviations. However, if, in A, informal interacting is cultivated, then de facto intangible deliverables will also be a contribution to the deliverable flowing to B. Illustrated is person “a” creating the intangible f(a) which will affect the value inherent in the deliverable.

Crucially, if Person “a” is replaced by, say, Person “g,” the latter will bring his or her own personal characteristics to the Roles 1 and 2, and the value inherent in the deliverable will be influenced accordingly.

For example, as we have already assumed that the results of creative activity reside in the intangible deliverables generated informally, and Person “g”’s transacting and personal characteristics will differ from Person “a”’s, we will end up with a different Deliverable flowing from A to B.

The question then arises: Is it ultimately beneficial to have a diverse mix of People in A, B and C?

In short, the answer depends on whether self-management is permitted and informal transacting is allowed to flourish, or even cultivated.

Furthermore, how people interact is also critical to outcomes. The simplest test for this is to study the different ways in which male and female human brains function and to recognize that there are significant differences (1)

It is also crucial that the level of Interacting between People catalyzes collaboration. This is in contrast to the worst of all worlds - coercion, where the latter is a key source of poor performance and unhappiness, with compliance following close behind. For more on human interactions see here in H5 3).

The "proof" uses the vocabulary VESvocab which underpins the Value Exchange System (VES).

In summary, VES paves the way in which the otherwise hidden connections (as informal networks) between Participants can lead to outstanding results within value-networked business ecosystems and associated business models. However, these results can be further enhanced by cultivating the diversity inherent in the way that male and female brains work.

A message for learners and cultivators of organizational intelligence:- Understanding the VES vocabulary will help you to fully grasp the principles and applications of the Value Exchange System (VES). By familiarizing yourself with its terms, you'll be better equipped to articulate its concepts, justify diversity in organizations, and apply the framework effectively to other challenges.

Images of man and woman generated by MS Copilot AI